What is it?

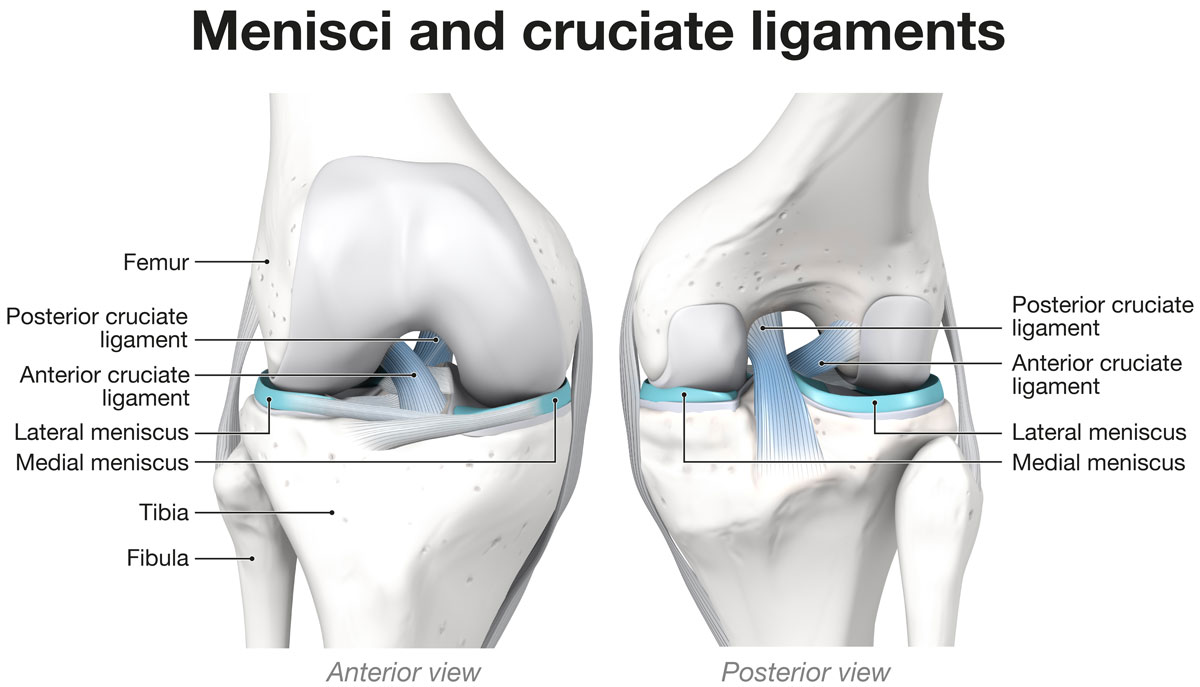

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a strong band of fibrous connective tissue located in the center of the knee. Together with the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), it provides stability to the joint during flexion–extension and rotational movements.

The ACL is subject to significant mechanical stress, particularly during sports, and may tear as a result.

Causes of ACL Injury

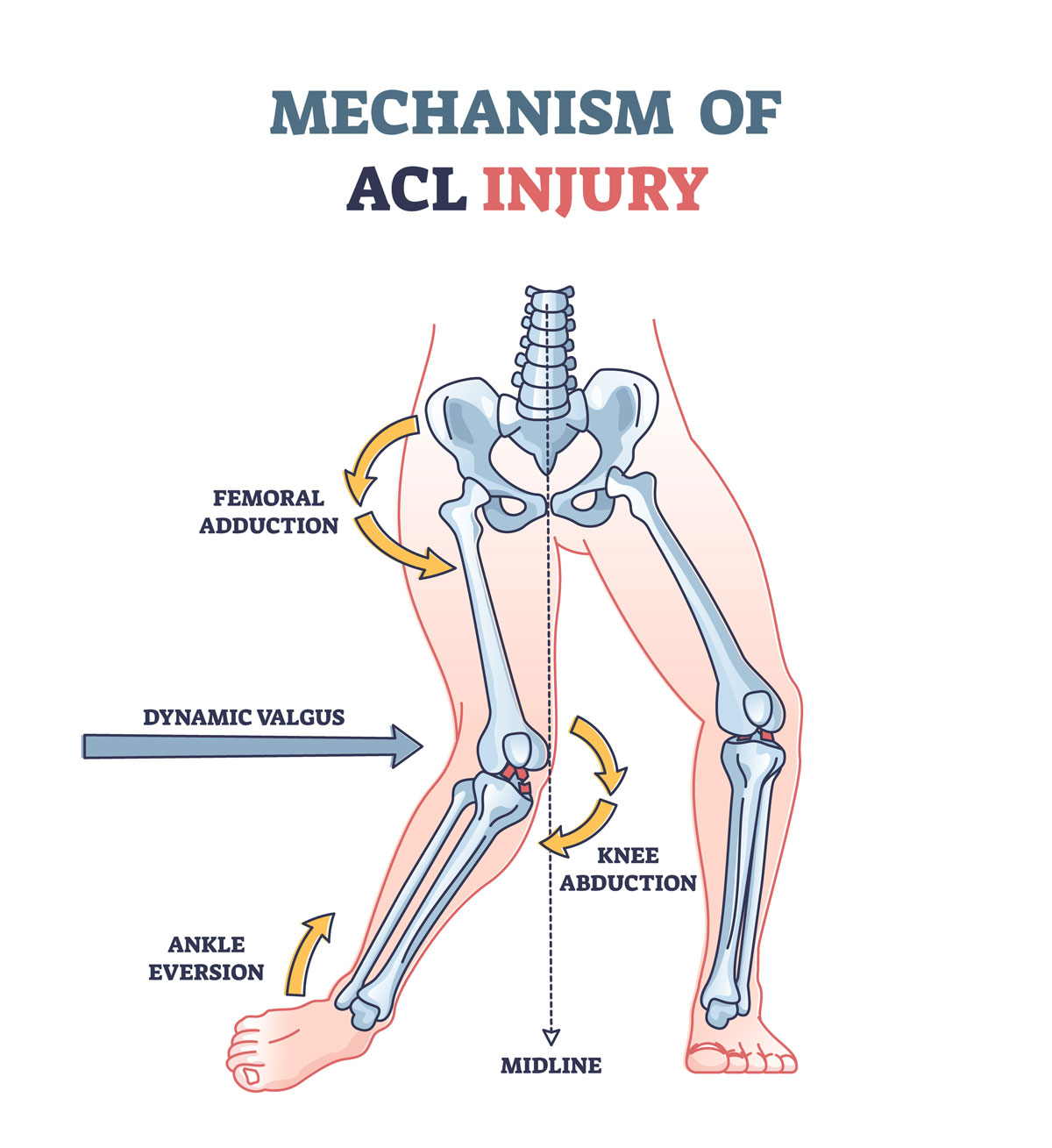

The most common mechanism of injury is a sudden valgus–external rotation movement while the foot is fixed on the ground. Sports with the highest risk include soccer, skiing, and basketball. Traffic accidents are the second most frequent cause of ACL tears.

The severity and type of injury—whether partial or complete—depend on the intensity of the trauma. ACL injuries are often associated with damage to other knee structures such as cartilage, menisci, or collateral ligaments.

Diagnosis

When an ACL tear occurs, patients often feel the knee “give way,” with the sensation that something has snapped or shifted inside the joint. Typical symptoms include pain, swelling, and limited range of motion.

Pain and swelling usually subside within about two weeks with rest, ice, and anti-inflammatory medication. However, instability often persists, preventing a safe return to sports activities.

Diagnosis is based on a physical examination, including specific tests to assess ligament laxity. Imaging tests complement the clinical evaluation:

- X-ray: to rule out fractures or associated bone lesions.

- MRI: to evaluate ligament, meniscal, and cartilage damage.

Treatment Options

The most appropriate treatment depends on several factors, including age, activity level, and lifestyle.

Even with an ACL tear, it is usually possible to carry out daily activities. However, sports—especially contact sports or those requiring rapid directional changes such as soccer, skiing, basketball, and volleyball—should be avoided.

An untreated complete tear leaves the knee vulnerable to further sprains, meniscal or cartilage injuries, and the development of early-onset osteoarthritis. For this reason, surgical treatment is generally recommended for younger and more active patients.

Surgical Treatment

ACL reconstruction surgery is a common procedure designed to replace the torn ligament with substitute tissue. This graft may come from the patient’s own tissue (autograft) or, less commonly, from a donor (allograft).

Autograft options include:

- The central portion of the patellar tendon (connecting the kneecap to the tibia)

- The hamstring tendons (gracilis and semitendinosus)

- The central portion of the quadriceps tendon

Today, ACL reconstruction is routinely performed using arthroscopic, minimally invasive techniques, often under regional anesthesia.

Rehabilitation is essential to restore full function and mobility of the knee. The rehabilitation program varies depending on the surgical technique and procedures used, but always emphasizes:

- Restoring full range of motion

- Regaining muscle strength in the lower limb

- Re-establishing maximum stability in single-leg stance through proprioceptive control

Rehabilitation with the Riva Method

An ACL tear causes a collapse of proprioceptive control, resulting in significant instability during single-leg stance. This increases the risk of recurrent sprains and accelerates the development of osteoarthritis.

Optimal outcomes—whether through surgery or a rehabilitation-only approach—depend on maximizing the patient’s functional stability, consistent with the anatomical condition of the ACL.

A Common Misconception

It is outdated to believe that functional knee stability can be restored through simple strengthening of the thigh and leg muscles. Stabilizing and directional muscle functions must be trained in their natural reflexive mode.

Using the Delos system to perform High-Frequency Proprioceptive Training (HPT) according to the Riva Method is the most powerful way to activate the stabilizing muscles of the lower limb.

The best results are achieved when patients complete 8 HPT sessions over 4 weeks before surgery, resuming training about 3 weeks post-operation. This approach provides two key advantages:

- Faster and higher-quality recovery – because the limb already reaches a higher level of stability before surgery, reducing mechanical stress during post-op rehabilitation.

- Improved biological healing – by shifting the knee from macro-instability to micro-instability, which promotes the biological transformation of tendon graft into ligament tissue (ligamentization).

This process also allows patients to make a more informed decision: whether to undergo surgery or continue with rehabilitation if the achieved level of functional stability is satisfactory.