What is it?

Achilles tendinitis, more accurately referred to as Achilles tendinopathy, is an overuse injury—a condition characterized by both inflammation and degeneration of the tendon. It develops when there is an imbalance between the mechanical load placed on the tendon and the tendon’s own structural tolerance. These two elements—mechanical stress and structural tolerance—are the final determinants that reflect the combined influence of all intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors, which we will examine in detail below.

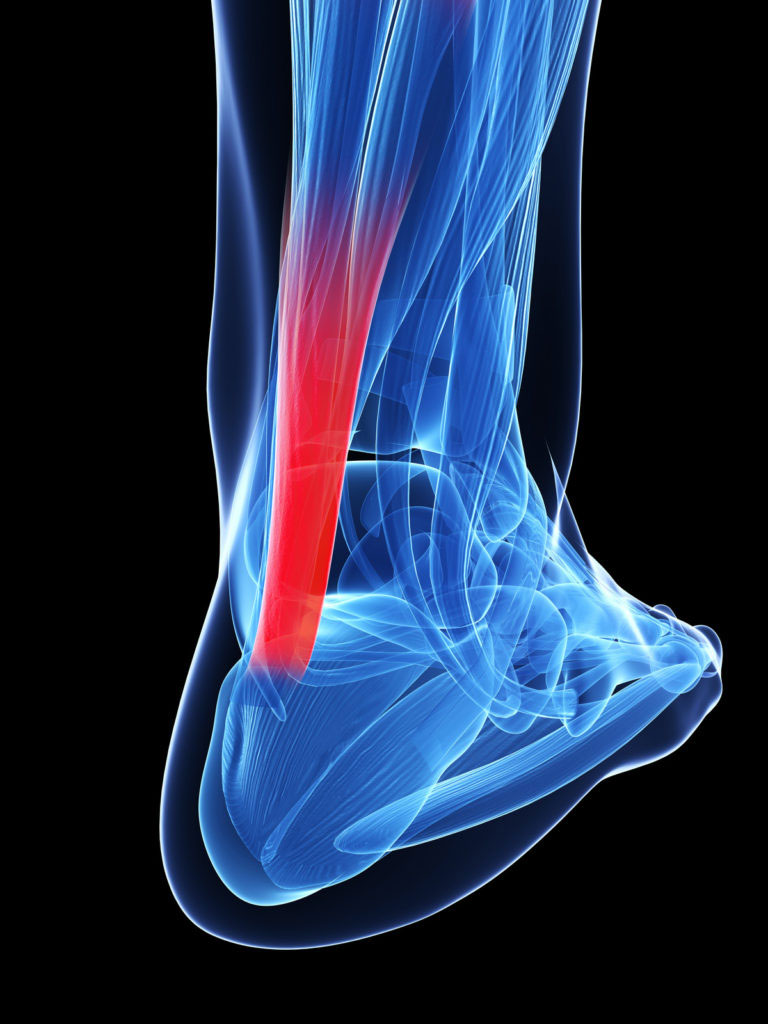

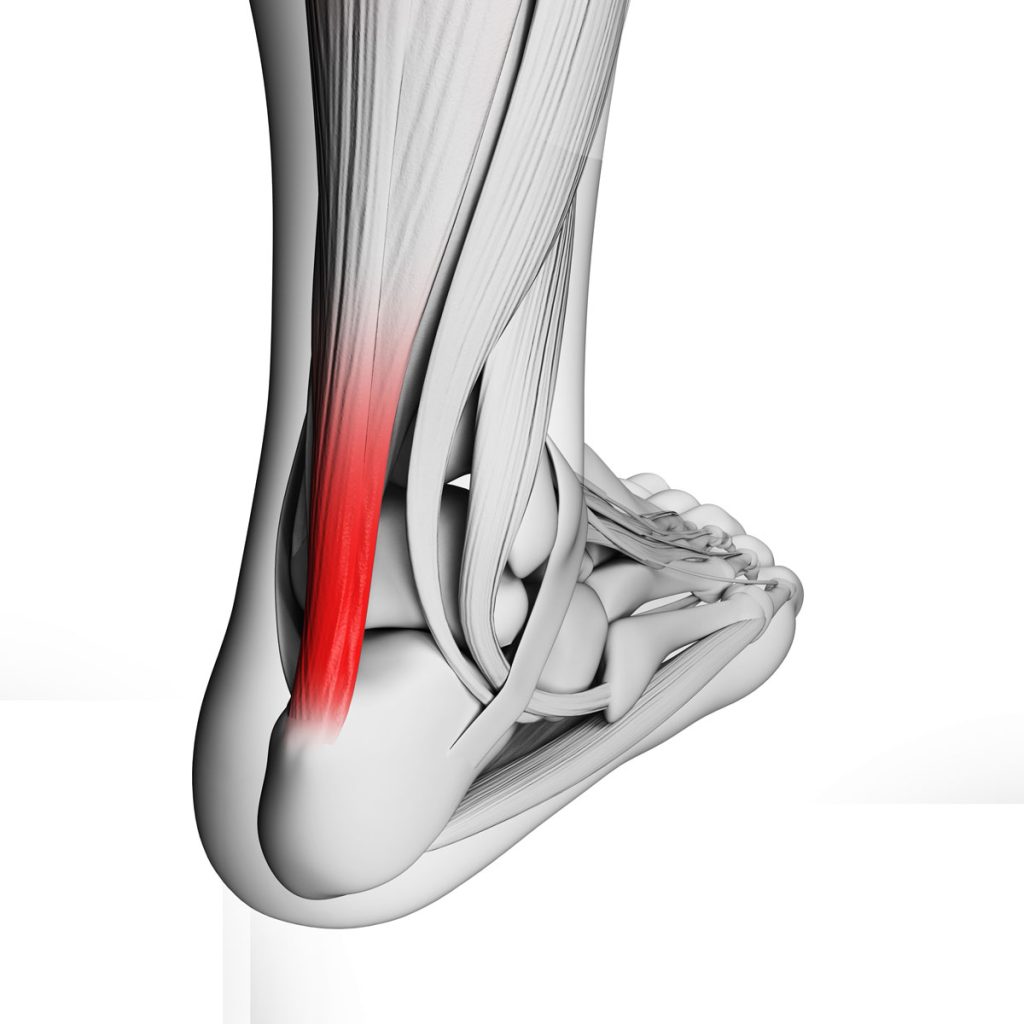

Anatomy

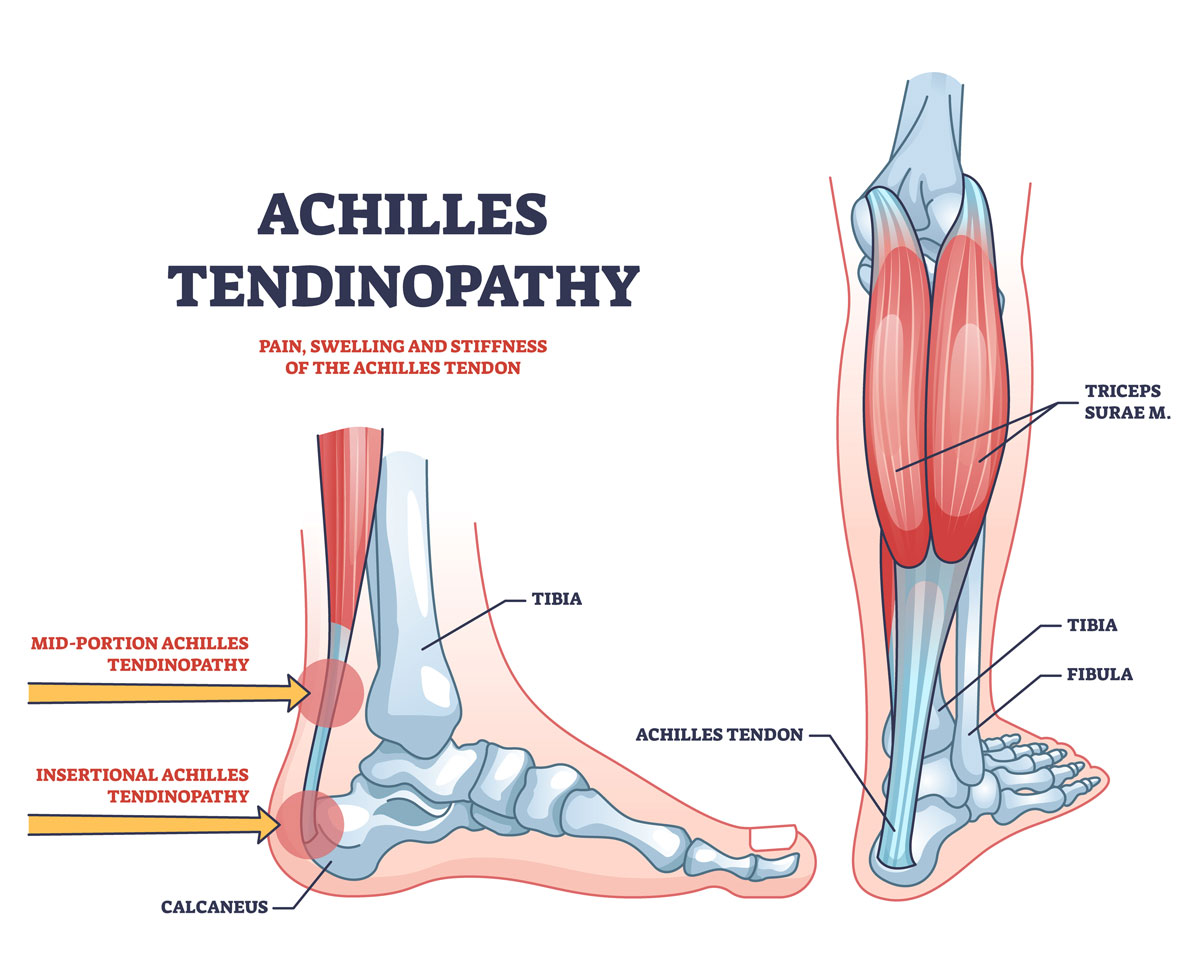

The Achilles tendon connects the calf muscles (the gastrocnemius and soleus) to the heel bone (calcaneus). In an average adult, it measures about 15 cm in length and 5–6 mm in thickness.

As it travels downward, the tendon narrows before widening again near its insertion. Typically, it reaches its narrowest point about 4 cm above the calcaneal tuberosity.

Just before inserting into the heel bone, there is a small synovial bursa (the retrocalcaneal bursa) filled with fluid, which reduces friction between adjacent anatomical structures.

Final Determinants

- Extrinsic–intrinsic determinant: The magnitude and frequency of mechanical stress generated by foot–ground interaction. Stress can be impulsive—large traction forces applied over a very short time with high injury potential—or repetitive—medium traction forces that individually may not cause damage but, when repeated tens of thousands of times, can exceed the tendon’s tolerance.

- Intrinsic determinant: The tendon’s reduced structural tolerance to mechanical loading, an increasingly common issue due to aging, metabolic conditions, or prior injuries.

Extrinsic Factors

- Footwear quality and design

- Training and competition surfaces

Intrinsic Factors

- Metabolic disorders, which may promote local inflammation

- Medication-induced tendon damage

- Aging, which reduces collagen metabolism, decreases cellular content, increases extracellular matrix, and lowers tolerance to mechanical stress

- Years of competitive activity

- Biomechanical alterations, such as excessive foot pronation during running, which places whipping stress on the Achilles tendon

A persistent Achilles tendinopathy may progress to tendinosis, a degenerative condition that can ultimately lead to tendon rupture due to loss of mechanical strength.

Achilles tendinopathy can occur either at the tendon’s insertion on the heel bone (insertional Achilles tendinopathy) or in the mid-portion, typically 3–6 cm above the heel, an area with relatively poor blood supply and therefore greater vulnerability to degeneration.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is both clinical and imaging-based. Clinical evaluation includes palpation and pressure testing of the Achilles region, gastrocnemius–soleus complex, and tendon insertion. Key assessments include muscle–tendon elasticity, strength, local pain, swelling, and tendon thickening.

Imaging studies that support diagnosis include ultrasound, X-rays, and MRI. Without appropriate treatment, the inflammatory process may become chronic, often leading to insertional calcifications visible on imaging.

Treatment

Healing time depends on the patient’s age, the duration of symptoms, and adherence to treatment. Recovery may take from two months to one year.

Conventional treatment includes:

- Rest

- Ice

- Anti-inflammatory physical therapies, such as high-power YAG laser therapy or TECAR therapy, which reduce inflammation, relieve pain, and ease muscle contractures

Shockwave therapy deserves special mention. Originally used in the 1990s for kidney stones, it is now widely applied to tendinopathies, delayed bone healing, muscle fibrosis, and osteonecrosis. Its benefits go beyond pain relief and anti-inflammatory effects: the stimulation of neoangiogenesis (new blood vessel formation) plays a central role in tendon healing.

The Riva Method

Anti-inflammatory treatments help manage symptoms but do not address the root cause of the problem.

If we compare tendinopathy to a fire fueled by a gas leak, anti-inflammatory therapies act like fire extinguishers: they reduce the flames but do not stop the fuel supply. To put out the fire completely, the source must be eliminated.

The Riva Method directly targets the causes driving Achilles tendinopathy. It works on both key determinants:

- Reduces the mechanical stress generated with every foot strike, thereby lowering strain on the tendon

- Increases the tendon’s resilience, enhancing its tolerance to both impulsive and repetitive mechanical loads

This dual effect progressively extinguishes inflammation and prevents recurrences. In practice, the tendon becomes stronger and more resilient while being subjected to lower levels of stress.

Recovery requires 2 to 6 months of systematic training with the Delos system, following the Riva Method. Chronic cases that have persisted for years may take longer, as longstanding structural changes in tendon tissue and the insertional region require extended remodeling time.