Low back pain—defined as pain in the lumbar region of the spine—is one of the most common causes of work absence and therefore carries a high socio-economic impact. About 80% of the population experiences it at least once in their lifetime.

Occupational risks for spinal injury are particularly relevant for workers performing heavy labor involving repeated lifting and trunk rotations. However, prolonged sitting and long hours of driving are also contributing factors in the onset of lumbar pain.

Anatomical Basis of Low Back Pain

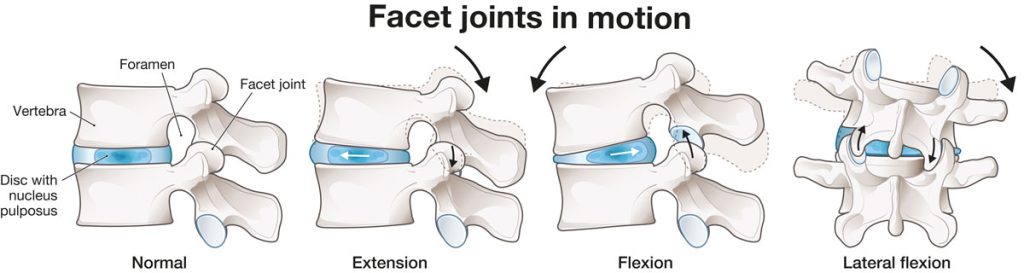

The vertebrae are separated by intervertebral discs—fibrocartilaginous structures that tolerate symmetrical axial loads well, but poorly withstand prolonged asymmetric pressures and torsional movements.

Degenerative disc disease is characterized by loss of hydration, leading to reduced height, strength, and elasticity of the discs. Over time, this results in varying degrees of segmental instability. Radial fissures of the annulus fibrosus often develop, which may progress to disc herniation.

The primary factors driving degenerative disc disease and secondary osteoarthritis are aging and mechanical stress—both static and dynamic. Dynamic factors (related to movement) appear far more significant than static ones (related to gravity). This is supported by the fact that similar spinal conditions (such as osteoarthritis and disc herniation) are also observed in quadrupeds, despite their horizontal spinal orientation.

Causes of Low Back Pain

In 90% of cases, low back pain is mechanical or musculoskeletal in origin. The most common pathogenic mechanism is mechanical instability of the spine, due to the deactivation of antigravity stabilizing systems. This instability progressively leads to disc and bone degeneration (spondyloarthrosis), along with profound structural and functional alterations of the muscular, ligamentous, and myofascial components.

The discs most frequently involved are those between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (L4-L5) and between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the first sacral vertebra (L5-S1).

Low back pain can be classified into three categories based on cause:

- Mechanical: includes nonspecific musculoskeletal causes, nerve root compression, disc degeneration, joint pathology, or vertebral fractures.

- Non-mechanical: due to tumors, inflammatory conditions (such as spondyloarthritis), or infections.

- Referred from internal organs: for example, biliary colic, kidney stones or infections, and aortic aneurysm.

Mechanical low back pain may also be aggravated by congenital abnormalities such as:

- Sacralization of the last lumbar vertebra (fusion with the first sacral vertebra)

- Spondylolysis (failure of fusion of part of the posterior vertebral arch)

- Spondylolisthesis (forward slippage of one vertebral body over another)

- Synostosis (fusion of two or more vertebrae).

Duration of Low Back Pain

In 85%–90% of cases, symptoms resolve within approximately three months. However, 40%–50% of these patients will experience recurrent episodes.

Diagnosis

Clinically, low back pain can be distinguished not only by duration (acute, recurrent, or chronic), but also by two fundamental mechanisms: neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain.

- Non-neuropathic pain arises from pain-sensitive spinal structures innervated by the sinuvertebral nerve of Luschka. Mechanical stimulation of these nerve endings, along with local inflammation, produces pain that often triggers reflex muscle spasm.

- Neuropathic pain, in contrast, follows the distribution of the affected nerve root compressed at its origin, and is often accompanied by changes in reflexes and sensory deficits.

Diagnosis is based on clinical history, physical examination, and instrumental tests such as X-rays, CT scans, MRI, and electromyography.

Aquatic Therapy

Aquatic therapy may play a role in the early, painful phase, but it is essential to emphasize that lumbar pain primarily arises from spinal instability in the Earth’s gravitational environment. The goal must therefore be to restore spinal stability and segmental alignment without relying on artificial stabilizers such as water. Anything that artificially stabilizes ultimately leads to destabilization. Furthermore, water reduces loading forces, which are essential for reactivating the automatic reflex mechanisms that govern spinal stability.

The Riva Method (Causal Treatment)

High Frequency Proprioceptive Training (HPT), as developed in the Riva Method, can naturally interrupt the pathogenic process that progressively increases spinal mechanical instability. It promotes the recovery of reflex-based proprioceptive stability and the correct realignment of spinal segments. Recent studies have shown that single-leg stance instability, caused by poor proprioceptive control, is highly predictive of future low back pain. Conversely, improving single-leg proprioceptive stability reduces the incidence of low back pain by 77.8%.

The meaning of these findings is clear: the spine cannot be stable unless it rests on a stable pelvis, which in turn requires stability in single-leg support. Ultimately, spinal health depends on the quality of foot-to-ground interaction.

The Riva Method is a potent activator of stability across the foot–lower limb–pelvis–spine system. Two weekly sessions of 45 minutes each with the Delos system, for 12 weeks, resolve the condition in nearly 80% of cases. A maintenance program of 6–8 weeks per year is usually sufficient to preserve—and even enhance—results.